Researchers Find Cellular Evidence Behind Lasting Immune Response in Some Cancer Survivors

Media contact: Ian Demsky, 734-764-2220 | Patients may contact Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

Resident memory T cells that enter a patient’s skin and blood during immunotherapy are behind the excellent and long-lasting immune responses to cancer that some survivors develop.

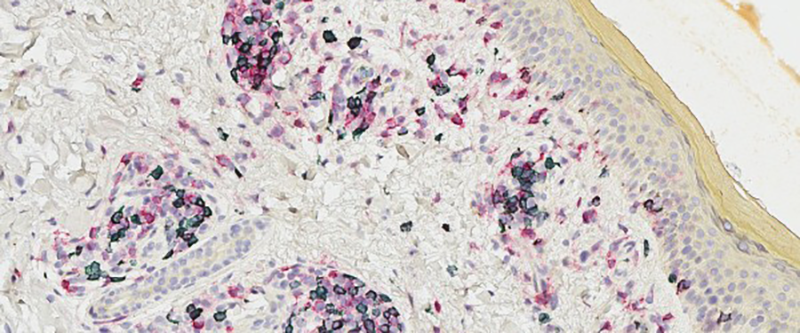

Credit: Shaofeng Yan

Some melanoma patients respond very well to immunotherapy, experiencing profound and durable tumor regression. A fraction of these patients will also develop autoimmunity against their normal melanocytes — skin pigment cells that give rise to melanoma — a phenomenon called vitiligo.

Melanoma survivors with vitiligo have long been recognized as a special group with an outstanding prognosis, and a strong response of immune system cells called T cells.

Now immunotherapy researchers at Dartmouth’s and Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Norris Cotton Cancer Center led by Mary Jo Turk, Ph.D., and surgical oncologist Christina Angeles, M.D. — now of the University of Michigan — have discovered how a subset of T cells known as memory T cells are generated in melanoma survivors with vitiligo and able to function for years after a tumor is gone.

“We are trying to understand how immune responses against cancer can persist over long periods of time in patients who have excellent responses to immunotherapy,” Turk says. “Our study was aimed at discovering where T cells go, what they do and how long they last in these patients. Some T cells last a short time, but others, known as memory T cells, can last for years. The goal of this work was to understand how memory T cells are generated in these patients.”

Angeles, an assistant professor of surgery at Michigan Medicine and member of the U-M Rogel Cancer Center, designed and led the clinical aspects of the study.

“We knew we had this group of patients who did better, who survived longer,” Angeles says. “We wanted to better understand and demonstrate why that was the case. This project moved us from studying these memory T cells in animal models into human patients.”

Turk’s and Angeles’ study found that T cells that enter melanoma tumors also have a tendency to enter a patient’s vitiligo-affected skin; that skin accumulates a more focused repertoire of tumor-related T cells than does blood; and that T cells in melanoma tumors are genetically and molecularly very similar to those in vitiligo-affected skin. With these findings, the research team then identified a new subset of “resident memory” (TRM) cells that localize to patient skin and tumor and make high levels of the cytokine interferon gamma. TRM-IFNγ cells have a unique gene expression profile, or “signature,” found in melanoma tumors from patients who have survived longer than those who don’t have the signature. Turk and Angeles found that T cells that infiltrate tumors have matching clonal partners, or daughter cells, that persist in patient skin and blood up to nine years later.

The team’s findings, entitled “Resident and circulating memory T cells persist for years in melanoma patients with durable responses to immunotherapy,” are newly published in Nature Cancer. No prior study has demonstrated cellular evidence of such long-lived immunity to cancer. The extensive collaboration between scientists, surgeons, and oncologists required harvesting tumors, blood, and skin from melanoma patients over a period of several years. Patient specimens were analyzed using state-of-the-art technologies called single cell RNA sequencing and T cell receptor sequencing.

These studies were done with a subset of T cells called cytotoxic or “CD8” T cells. And continuing work at both U-M and Dartmouth will seek to understand if similar features are seen in patient-helper or “CD4” T cells, and if similar immunity is generated in patients with skin inflammation aside from vitiligo, such as rash. The team will also investigate how different types of immunotherapy affect the new cell population that they discovered. “Finding that T cells can persist for years throughout skin and blood and understanding what defines such durable immune responses in melanoma patients will lead to better design of therapies to achieve such responses,” says Turk.

Additionally, Angeles adds, the researchers want to better understand why this response following immunotherapy treatment arises in patients with melanoma, but not in other types of cancer.

“Across cancer types, there are autoimmune side effects that occur in patients following immunotherapy and many of them are quite detrimental,” she says. “So if we can understand why this side effect we see in this subset of patients with melanoma is protective, perhaps we can learn things that could apply in other types of cancer.”

Courtesy of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, adapted with permission