U-M researchers develop an enhanced communication framework for use in the cancer clinic

Media contact: Elizabeth Katz | Patients may contact Cancer AnswerLine™ 800-865-1125

Authors account for both verbal and nonverbal communication among doctors, medical staff and cancer patients.

Cancer doctors and their medical colleagues are frequently tasked with breaking negative news to patients who have been diagnosed with any of the 600-some known types of cancer. Researchers from the University of Michigan and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln have proposed an enhanced model of communication focusing not only on what is said in the clinic but also nonverbal communication of the doctor and how doctors in turn interpret patients’ nonverbal cues.

Timothy C. Guetterman, Ph.D.

Credit: Michigan Medicine

The paper, “Incorporating verbal and nonverbal aspects to enhance a model of patient communication in cancer care: A grounded theory study,” was recently published in the journal, Cancer Medicine. First author is Timothy C. Guetterman, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine; Rae Sakakibara, and Srikar Baireddy, all from the University of Michigan, and Professor Wayne A. Babchuk, Ph.D., of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

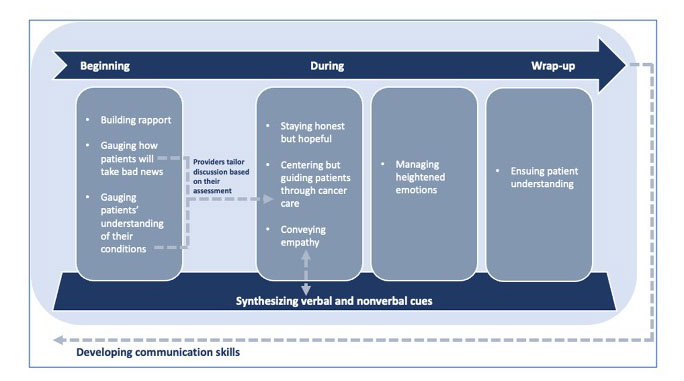

The study aimed to develop a conceptual model of communication that accounts for nonverbal communication, such as ‘mirroring,’ silence, distance, smiling, nodding and leaning. The authors assert that nonverbal communication is an area of study that lacks exploration on its impact on how medical staff can communicate with patients in an effective and empathetic way in often-stressful situations.

Included in the team’s enhanced framework, based on the grounded theory model of communication in cancer care, includes the main tenets of responding to emotions, exchanging information, making decisions, fostering healing relationships, enabling patient self-management and managing uncertainty.

“A key difference is that our model, derived from views of cancer care providers, is organized into a process in which providers learn from each visit,” they write. “The present research extends the existing models by organizing important aspects of verbal and nonverbal communication into the process of an encounter.”

As part of the study process, the team interviewed 23 providers, including nurses, physicians, surgeons and physician’s assistants. The team focused on major themes that can present during the clinical encounter, from beginning to wrap-up, including:

- Building rapport with patients

- Gauging how patients will take bad news

- Ensuring patients’ understanding of their conditions

- Staying honest but hopeful

- Centering but guiding patients through cancer care

- Conveying empathy while managing heightened emotions

- Ensuring patient understanding

Credit: Michigan Medicine

Study participants’ answered semi-structured questions that elicited qualitative data, allowing researchers to explicate how the providers approach a patient’s interactions as they relate to the various themes in the study, both verbally and nonverbally.

For example, one participant, when asked about how they build rapport with a patient, responded: “I try to use open body language. I try to be mindful to not cross my arms and my legs when I’m in the room.”

Another participating doctor, when asked about how they gauge how patients will accept bad news, said:

“Number one, it was how well I know the patient and they know me, like how long they’ve been under my care. I think that has two roles. One is, the more comfortable they are, they may be more comfortable allowing themselves to sort of emote, break down. At the same time, they may emote less because they know I’m here for them and that they have someone who was going to be here for them because I’ve been there for them before.”

The authors write that understanding provider experiences and perspectives with communication in potentially emotionally intensive encounters, such as communicating results or bad news to cancer patients, is needed to inform patient-centered interventions.

“Providers’ firsthand perspectives of intentional verbal and nonverbal communication are needed to further refine the patient-centered communication framework,” they write.

The authors note that a portion of their results suggested that providers were not often cognizant of their nonverbal behavior nor how they interpret patient’s nonverbal behavior although questions prompted them to consider that topic in depth. For example, one participant — a seasoned doctor — was asked about patients’ responses to the doctor’s own body language. The doctor responded, “I don’t know that I can answer that question.”

“The results provide a framework to think about and attend to nonverbal communication throughout an encounter, which is particularly important given the role of nonverbal behavior in building rapport, improving patient satisfaction, and enhancing patient engagement,” Guetterman et al write.

Article citation: Guetterman, T. C., Sakakibara, R., Baireddy, S., & Babchuk, W. A. (2024a). Incorporating verbal and nonverbal aspects to enhance a model of patient communication in cancer care: A grounded theory study. Cancer Medicine, 13(14). https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.70010.