Postdocs are critical to the success of cancer research

Media contact: Ian Demsky, 734-764-2220 | Patients may contact Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

Meet some of the men and women helping push scientific discovery forward at the Rogel Cancer Center

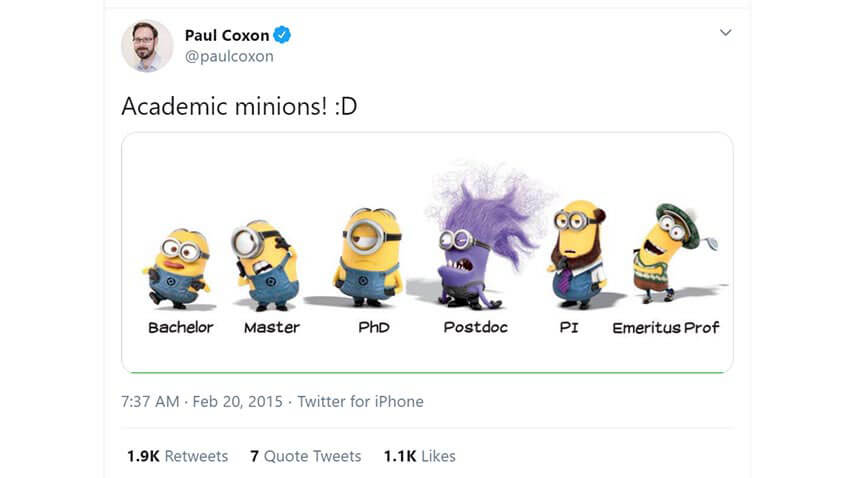

In the winter of 2015, Paul Coxon, Ph.D., a physicist at Cambridge University tweeted a meme that assigned academic roles to Minions from the popular movie franchise.

In it, a Ph.D. minion gives a cool side-eye to a fearful master’s minion and an oblivious bachelor’s minion. The principal investigator minion stands looking world-weary as the emeritus professor golfs. But it’s the postdoc who leaps off the screen -- purple when all his fellows are yellow, with a grizzled visage and chaotic, untamed hair.

“I think the image is perfect,” says Andrea Comba, Ph.D., a postdoc in the lab of Pedro Lowenstein, M.D., Ph.D., at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center. “We are motivated by our passion for research, but there are many things that you need to accomplish in a short period, so yes, sometimes it can feel like too much.”

Postdoctoral training is to bench scientists what residency programs are to medical students -- a period of mentored apprenticeship to bridge the gap between one’s student years and an independent career.

Postdocs spend several years in the lab of a senior researcher focused on not only honing their science, but also on developing softer skills: finding and nurturing collaborations, mentoring undergrads and grad students, grant writing, learning how to manage project budgets and finances, distilling research findings into journal articles. Next to their mentors, they often serve as a lab’s most seasoned scientists.

“Postdocs are a vital part of the engine of discovery science,” says Maria Castro, Ph.D., a professor of neurosurgery and cell and developmental biology, whose joint lab with Lowenstein focuses on the cellular and molecular biology of malignant brain tumors, and on translating their discoveries at the bench into new treatments. “Now, that engine is large and has many parts, but postdocs are a critical component to that engine. They bring a lot of energy, a lot of expertise and a lot of new ideas to a lab.”

Postdoctoral research fellows exist in a weird liminal state, however -- no longer graduate students upon whom academic attention and resources are focused, yet still under the wing of a principal investigator and without true independence. As a result, their accomplishments and contributions may go unheralded, if not unnoticed.

“They’re a group of people we need to do more for,” says Amanda Garner, Ph.D., an associate professor of medicinal chemistry at the U-M College of Pharmacy and a member of the Rogel Cancer Center. “They are everything in the lab. They don’t have as much experience, but are really at the level of a peer scientist to their mentor.”

Additionally, she says, more so than graduate students, postdocs come into a given lab because they really want to be there.

“That sense of drive and belonging and ownership can make a big difference,” she says.

Garner’s sentiment is backed up by a 2019 study that examined improvements in graduate students’ research skills, finding that mentoring and engagement from postdocs had an outsized influence on junior lab members. The authors concluded that postdocs “disproportionately enhance the doctoral training enterprise, despite typically having no formal mentorship role.”

“Many PIs travel extensively to secure funds and raise the prestige of the lab,” the study’s senior author, David Feldon, Ph.D., of Utah State University, told Chemistry World. “This often means that the postdocs are the ones working ‘elbow-to-elbow’ at the bench and are the ones available for ongoing, just-in-time mentoring.” Adding to that, recent changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic mean investigators are spending even less time in their labs than before.

While postdocs undeniably have a lot on their shoulders -- with long hours, relatively low pay and the pressure to hit a scientific home run that will launch their careers -- they’re also uniquely positioned, says Costas Lyssiotis, Ph.D., an assistant professor of molecular and integrative physiology and of internal medicine whose lab studies how cancer rewires metabolism.

“They have a trial run at independence from within the safety of a being in someone else’s lab,” he says. “It’s a time to develop their own ideas and test them without some of the financial pressures and other pressures that can come later.”

At the Rogel Cancer Center, recruiting great postdocs means not only bringing in people who are top-notch scientists, but also women and men who bring diverse backgrounds, viewpoints, skills, and interests to the research enterprise, and who exemplify the cancer center’s collaborative, team-science spirit, says Director Eric Fearon, M.D., Ph.D.

“We’re looking for trainees who are dedicated to advancing knowledge relevant to the cancer problem and to improving cancer outcomes,” he says. “Our goal is not just to train the next generation of cancer researchers, but to train the next generation of leaders in the field.”

Meet Some Fellows

Today there are more than 50 postdocs working in the labs of Rogel Cancer Center members across U-M.

Originally from Argentina, Comba, of the Lowenstein lab, came to the cancer center in 2016 after finishing her Ph.D. work in molecular biology at the National University of Cordoba, where she also did an initial, two-year postdoctoral fellowship.

“The decision to come to America wasn’t an easy one, but we were excited about the opportunities it presented for us,” Comba says.

The Lowenstein group had exactly what she was looking for in a training lab -- she would be able to focus on the molecular mechanisms of brain tumors and also get experience moving bench discoveries to the clinic; the group is leading a clinical trial at U-M to test the use of gene therapy to attack glioblastoma, an extremely aggressive form of brain cancer. The lab also had a great track record, frequently publishing in leading scientific journals.

Over the last four years, Comba has been involved in several research projects, including an ongoing series of papers investigating novel multicellular structures within gliomas that the group discovered and dubbed “oncostreams” -- and for which she is developing new imaging techniques to study the structures’ dynamics.

“In the beginning, you’re really focused on your projects and experiments, but eventually you realize all the other skills you need to work on, too,” Comba says.

Comba received a Postdoctoral Translational Scholars Program career development award from the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research, which included coursework and clinical immersion along with workshops in public speaking, responding to peer review and navigating the hurdles of standing up a translational approach or an early-stage clinical trial.

The U-M Medical School as a whole consistently ranks high for training and career development support -- in the top five institutions when it comes to T, K and F grants, though it ranks ninth for National Institutes of Health funding overall.

Some postdoctoral fellows, like Nneka Mbah, Ph.D., know they want to be scientists at an early age.

“When I was in high school, I recall watching a particular documentary where at the end the narrator was like, ‘this is what the biochemists do in the lab’ -- and I thought, that’s it, done, this is exactly what I want to do,” she says. “I want to work in the lab. I want to understand disease at the molecular and cellular level.”

Mbah, who grew up in Nigeria, came to Michigan in 2017 after earning her doctorate in cancer biology at the University of Toledo. Her work at U-M on fatal childhood brain stem tumors called diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas, or DIPG, earned her a prestigious Chad Tough/Defeat DIPG postdoctoral fellowship and led to her selection as a 2019 Forbeck Scholar.

“With my background in brain tumor biology and now studying pediatric brain tumors, it’s been very fascinating, very challenging and very exciting to understand the nature of DIPG and come up with ways to therapeutically target it,” she says. “Twenty years ago, there was really very little done in that space, but with recent advances, the field is making tremendous progress in understanding its pathogenesis. And I love the feeling that now we are not too far away from coming up with some novel targets and approaches that could really make a difference in this deadly disease.”

‘Sometimes I feel like I’m back in undergrad’

For Emilio Cardenas, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in Garner’s lab, the goal was to take his background in synthetic chemistry in a new, more translational direction.

“An odd thing about scientists in general -- we like to stay in our little bubbles, and it’s difficult to leave those sometimes and venture into unfamiliar areas,” he says. “But that’s what I looked for when I was looking for postdoctoral positions.”

Cardenas, who grew up in a small farming community of 6,500 in California’s central valley, is one of the first in his family to earn a college degree and the first to earn a doctorate. After completing an undergraduate degree in chemistry at California State University in Fresno, just 15 minutes from his hometown, he attended Purdue University. He did his doctoral research in a lab that focused on Alzheimer’s disease and HIV.

A routine lunch with a visiting seminar speaker -- Garner -- blossomed into a postdoc opportunity several years later.

“It’s really funny how those kinds of everyday interactions can change your life,” he says. “You talk to someone for a few minutes and don’t really think much more about it — never imagining that three years down the road you’d be in their lab.”

Garner’s group is focused on finding new ways to attack cancer and metabolic diseases through difficult to target protein-protein interactions and RNAs.

“Targeting RNA for therapeutic purposes is really cutting edge right now, a new frontier, so that was exciting to me,” Cardenas says. “The challenge of being able to apply my background in synthetic chemistry to the enigma of targeting RNA with small molecules was exciting to me. Attempting to wrap my head around some biology concepts, sometimes I feel like I’m back in undergrad -- however, those feelings serve as a humbling reminder that every difficult question is an opportunity to learn.”

This diversity of thought and experience is something Garner cultivates in her lab.

“When it comes to cancer research, we need all the different approaches we can get,” she says. “Someone with a different scientific background can bring fresh eyes to a project and help come up with creative solutions to challenging scientific problems. We should encourage that as much as we can.”

Mahmoud Alghamri, Ph.D., brought a background in pharmacology to Castro’s lab at the Rogel Cancer Center.

Alghamri, a Palestinian who grew up in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, actually started his career as a pharmacist after graduating from Al-Azhar University in Gaza.

“But I didn’t really like practicing pharmacy and I was passionate to work in science,” he says. “I was looking for opportunities and started applying to multiple scholarships.”

Alghamri was awarded a prestigious Fulbright scholarship in 2011, allowing him to pursue a master’s degree and ultimately a doctorate in molecular pharmacology and toxicology at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. He also pursued board certification and licensure as a pharmacist in the state of Michigan and Ohio.

“After obtaining my Ph.D., the field of cancer immunology was really starting to grow exponentially,” Alghamri says. “I said to myself, ‘I have to join this field.’”

He joined Castro’s lab at U-M in 2016, working on novel gene therapy to stimulate the body’s immune response against brain cancer.

“My work was focused on a common mutation in an enzyme called isocitrate dehydrogenase, or IDH,” Alghamri says. “A mutation in this enzyme occurs in almost 55% of glioma patients, and the patients who have this mutation survive longer, but exactly why this is the case had not previously been clear.”

He hypothesized that the mutation caused a change in gliomas that enhanced the body’s response against the tumors. His research, which is under revision at a leading cancer journal, showed that, indeed, there were important differences in the tumor suppressor cells in patients and animal models bearing the IDH mutation compare to those who do not have the mutation.

Especially with a lot of university hiring on hold due to COVID, Alghamri says he’s open to future career opportunities in both academia and industry.

“I don’t think the public fully understands how challenging scientific discovery really is,” he says. “People look at the end product -- like clinical trial results -- but they have no idea how much time and effort and suffering had to be done to get to that point.”

What makes a good postdoc?

Scientists -- especially young scientists -- are by nature and training adept at integrating new skills, new tools and new perspectives into their work. So, in many cases, faculty members are focused less on a trainee’s scientific background than one might imagine.

“When I recruit someone to the lab, I don’t look so much at their expertise or their training in any particular area,” says Castro. “What I do is I pay a lot of attention to their attitude. Anything can be learned. The issue is do you have the right attitude and the passion for what you’re doing?

“They also need to bring in new ideas, new angles, a new vision to the project,” she adds. “I’m looking for someone who can be creative and be a partner in pushing the project forward.”

Lowenstein agrees. His nibbling-around-the-edges approach to interviewing a prospective recruit aims for an understanding of the postdoc beyond the four corners of their curriculum vitae.

“I try to look for imagination,” he says. “Someone may tell you they’re very interested in cancer. They’ve done their Ph.D. in cancer. And you ask them, well, OK fine, how would you cure cancer? And most of the answers you get are things that have already been tried and didn’t work. There are no wrong answers, but I want to see where does your mind take you if money and time aren’t a limitation?”

This bountifulness of spirit is important, Lowenstein says, because the transition between a doctoral degree and a postdoctoral fellowship is a rare opportunity in the life of a scientist.

“I always tell my students that they have a great opportunity when they finish their Ph.D. to really do anything,” he says. “It’s a very open moment. You could have studied biology, but you can decide you want to work on public health or bioinformatics or whatever -- go in any direction. But once you decide on that direction, you should be really sure that is the direction you want to go in -- and then put 150% of your effort into it.”