Few patients receive recommended genetic testing after cancer diagnosis

Courtesy Stanford Medicine | Media contact: Nicole Fawcett, 734-764-2220 | Patients may contact Cancer AnswerLine™ 800-865-1125

A new study finds surprisingly low genetic testing rates for cancer patients who may benefit, especially among Asian, Black and Hispanic patients.

Knowing that you’ve inherited genetic mutations that increase the risk of cancer can help you catch the disease earlier, and if diagnosed, choose the most effective treatments. But despite guidelines that recommend genetic testing for the majority of cancer patients, far too few are tested, according to new research by University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center scientists and collaborators.

Among more than a million patients with cancer, only 6.8% underwent germline genetic testing — an analysis of inherited genes — within two years of diagnosis, according to the study published June 5 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The rates were particularly low among Asian, Black and Hispanic patients.

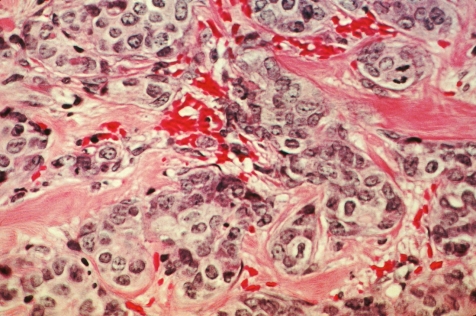

Photo credit: Stanford Medicine

“When we’re talking about cancer risk, germline genetic testing looks specifically at the genes that, if altered in a way that is harmful, give people a much higher risk of cancer than the average person,” said Allison Kurian, M.D., professor of epidemiology and population health at Stanford Medicine, who is the lead author of the study.

“Increasingly, we’re seeing that germline genetic testing matters in terms of selecting a medication or surgical treatment that might be best for a patient,” she added.

Some cancer drugs, such as PARP (poly-ADP ribose polymerase) inhibitors, which target DNA repair in cancer cells, are more effective in people with certain gene variants. And patients with high-risk genes — as well as their relatives — can benefit from more preventive screening.

Germline genetic testing, which can be done on saliva, is more accessible and less costly than ever, and widely recommended in the medical literature, Kurian said.

‘Surprisingly low’

Photo credit: Cecil Fox, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

Kurian wondered how many patients were actually getting these tests, so she and colleagues used data from statewide cancer registries in Georgia and California, which capture nearly all cancer diagnoses in these states. They focused on breast, colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate and lung cancers.

Of 1,369,602 adult patients diagnosed with cancer between 2013 and 2019, only 6.8% received germline genetic testing within two years of their diagnosis. “It’s a surprisingly low rate,” Kurian said.

Even patients who had cancer types with the highest testing rates — male breast (50%), ovarian (38.6%) and female breast (26%) mdash; were not tested as often as guidelines recommend. Male breast cancer, which strongly suggests an inherited gene variant, and ovarian cancer, which is highly lethal, warrant testing in all cases, Kurian said.

“These are not controversial,” she said. “These are not situations where some people think these patients should be tested and some people think they shouldn’t. They clearly should be.”

Although this study did not examine the reasons behind low test rates, prior studies suggest some cancer patients do not receive information about genetic testing from their physicians. “There may be a component of patients not getting the advice they need to get tested,” Kurian said.

Racial disparities

The study uncovered racial and ethnic disparities. Among all patients with male breast, female breast and ovarian cancer — only 25% of Asian, Black and Hispanic patients received testing, compared with 31% of non-Hispanic white patients.

Even as overall testing rates increased from 2013 to 2019, the gap between different groups did not narrow.

Asian, Black and Hispanic patients also were more likely to receive uncertain results, which are gene variants that differ from the normal gene but have not been linked to cancer risk. That’s likely due to less genetic research in these populations to establish normal versus pathogenic variations.

“Uncertain results are more common in populations and groups of people who haven’t had as much access to testing because we haven’t gotten a sense of the full range of what’s normal for those populations,” Kurian said. “It’s all about whose genes were sequenced and defined as normal.”

More genes, more uncertainty

Over the study period, the number of genes tested for increased from a median of 2 to 34, as scientists identified more genes associated with cancer. The inclusion of newer, less-studied genes increased uncertain results for all groups, but particularly for Asian, Black and Hispanic patients.

The vast majority of uncertain results will eventually be categorized as normal, so they should not be treated as pathogenic, Kurian said. She added that mismanagement of uncertain results is another burden that may fall more heavily on people with less access to quality care, further compounding disparities.

“We need more research to improve the accuracy of test results, especially among populations who have had less access to genetic testing and research,” she said. “We also need to understand how the results influence perceptions of cancer risk and behavior.”

The new findings reveal that reality does not meet expectations when it comes to genetic testing for cancer, but they also give a sense of specific deficits and possible solutions. Telemedicine and samples sent by mail could make testing available to people in more remote areas, for example. Better insurance coverage and more education for provider and patients could also increase testing rates.

“We have shown that testing results often come too late to inform cancer management,” said Steven Katz, MD, professor of medicine and of health management and policy at the University of Michigan and the senior author of the study. “It’s not just about getting a test — it’s about integrating results into cancer management and prevention for patients and their families to save lives.”

Researchers from Emory University; the University of Southern California; the University of California, San Francisco; Ambry Genetics; GeneDx; Invitae; and Myriad Genetics also contributed to the study.

The study was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 CA225697, P01 CA163233, P30 CA046592, HHSN261201800003I, HHSN26100001, HHSN261201800032I, HHSN261201800015 and HHSN261201800009I), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the California Department of Public Health.