The next generation

contributed by Nicole Fawcett, Staci Vernick and Eric Olsen

The future of cancer research

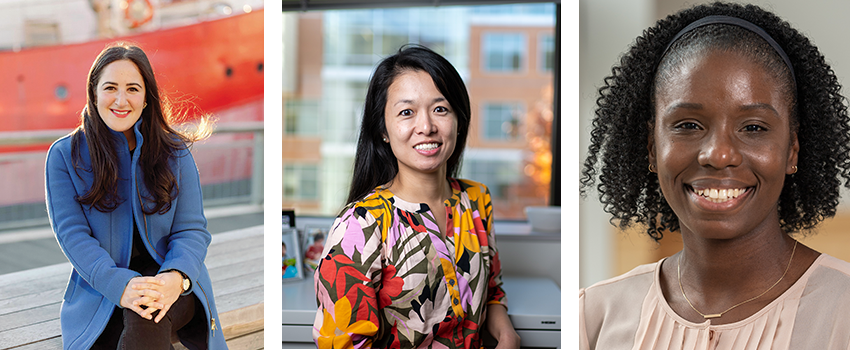

Credit: Michigan Medicine

Asking the right questions: Lauren Ghazal, Ph.D., FNP-BC

Postdoctoral fellow Lauren Ghazal’s training as a nurse and experiences as a cancer survivor shape her research and desire to help young adults with cancer

Lauren Ghazal, Ph.D., FNP-BC, is used to juggling multiple roles. From the time she started nursing school, she knew she wanted to be both a practicing nurse and a researcher. Then she added one more role: cancer survivor. "It completely shifted me to studying cancer survivorship," says Ghazal of her Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosis.

"I had these views as a provider and as a researcher, and now as a young adult cancer patient. It has helped me shape research questions in a unique way because I have this embodied experience of studying what I've also lived."

Ghazal, a post-doctoral fellow in cancer care delivery research, drew from her own experience to ask questions unique to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: Why is it so difficult to navigate the health care system? How do people manage work and careers with complications from treatment? How do they understand their health insurance and avoid medical debt?

Her research uncovered what she termed the "Survivors’ Dilemma.” The young adults in cancer treatment she interviewed were just beginning their careers or still completing their education. After cancer, they questioned whether they could physically or mentally do the job, whether they felt called to change career focus, and whether they could afford the cost of education or the prospect of leaving a job.

"All three of those questions completely affected one’s quality of life," Ghazal says. "So, are there things we can target to mitigate financial hardship or to improve cognizant function at work?"

One avenue Ghazal would like to explore is vocational rehabilitation, where cancer survivors are connected with a counselor to help navigate questions around disclosing a

diagnosis or balancing symptoms with work demands.

"These issues came up multiple times as a source of distress for cancer survivors. This is something we can help survivors with. By providing this information and these resources, we can improve their quality of life," Ghazal says. For example, an unexpected benefit of the pandemic is that remote work is more widely accepted. For a cancer survivor, calling in via Zoom could become a crucial accommodation.

The tie between financial hardship and cancer survivorship is a unique fit for Ghazal, who initially studied economics and planned to become a lawyer. A semester abroad exposed her to health care delivery systems and she came home to tell her mom, who is a nurse, that she wanted to go into nursing.

During her cancer treatment, she found herself doing late-night searches for any research on young adult cancer survivors. At that time, there was a growing body of work, some of it led by Bradley Zebrack, Ph.D., M.S.W., M.P.H., professor of social work at the University of Michigan.

Today, Zebrack is one of Ghazal’s mentors. She also works with the Rogel Cancer Center’s recently formed Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Team. Geared toward ages 13 to 39, the initiative includes physicians, social workers and researchers with expertise in adult, adolescent or pediatric medicine.

"I would never have gotten to this point in my research career without my cancer diagnosis and experience," Ghazal says. "Now I need to ask the right questions and make sure the work I'm doing is addressing what AYAs actually want and need. It has to have a meaningful impact."

The power of why: Angel Qin, M.D.

As a child, Angel Qin’s near constant refrain as she explored the world was, "Why?"

Today, the medical oncologist specializing in lung cancer still asks a question that has guided her throughout her medical training and is rooted in this early curiosity: Why do some patients become resistant to treatment while others don't? Angel Qin, M.D., is a clinical assistant professor of hematology/oncology at Rogel and a member of its Emerging Leaders Council. She leads several clinical trials that hold potential to improve the standard of care for advanced stage lung cancer as she actively engages in shaping the future of Rogel and its next generation of leaders.

Qin has always been interested in understanding the human immune system. "This phenomenal system of cells – like killer T cells and macrophages – defends us from bacteria, viruses and fungus trying to harm us on a daily basis," she says. "We have this fascinating universe inside us."

Qin was born in China and came to the U.S. when she was 8. During medical school and residency at Case Western Reserve University, Qin viewed studying clinical oncology as a privileged opportunity to connect with patients during the life-changing moment of hearing a cancer diagnosis, and to walk with them in the intimate journey that follows.

Qin says she found her true calling when she joined U-M in 2015 for a hematology/oncology fellowship. At the time, cancer immunotherapy was a nascent field, and Qin seized the opportunity to combine her interests in immunology and oncology in this exciting new direction.

"We are also increasingly realizing the dream of personalized medicine in lung cancer," she says. "There are 10 approved targeted therapies and overall survival rates are improving. The problem though, is that eventually the lung cancer gets smart and overcomes whatever treatment we've offered."

This mystery of treatment resistance is the big "why" driving Qin's research today.

Co-chair of Rogel's clinical research team for lung cancer, Qin is the principal investigator on several clinical trials currently underway, including a multi-site study to determine whether adding a PARP inhibitor to standard of care combination chemotherapy and immunotherapy can improve survival in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. For her work, Qin was named a 2021 Rogel Young Clinical Investigator, an award that recognizes faculty for outstanding clinical research and a promising future in oncology.

On Rogel's Emerging Leaders Council, Qin and her colleagues work closely with cancer center leadership to advocate on behalf of early career faculty and identify high priority issues and research opportunities that will advance Rogel’s mission.

"We collaborate on ways to improve the cancer center from many different perspectives – clinical operations, education, training, outreach – and put forth our vision for the institution,” Qin says. To her, it is a unique opportunity to gain valuable first-hand experience in what it takes to lead one of the nation's top NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers.

Qin also serves as the clinical lead on a large, multidisciplinary research initiative to develop more effective treatment strategies for lung cancer patients diagnosed with alterations in the ALK gene. The focus of the research, Qin says, is to understand the biological pathways that drive an individual patient's cancer—why the disease grows the way it does.

"We're trying to understand disease progression at every step from the stem cells to multi-drug resistant cells to guide personalized treatment and develop new therapies."

Continue reading Illuminate, 2023 or download the print version.

Minimally Invasive Robotic Surgery: Donnele Daley, M.D.

As a trained engineer, oncologic surgeon Donnele Daley brings a technical perspective to cancer surgery.

As a child growing up in Jamaica and the Caribbean, Donnele Daley, M.D., aspired to have a career in the applied sciences. She moved to the U.S. for college, where she

studied engineering, physics, and mathematics.

"My plan was to go into biomedical engineering," she says. It wasn't until I worked with a surgeon on implant designs that I got more interested in medicine." Toward the

end of her degree, she decided to go to medical school. She was particularly interested in surgery. "I was always a very technical person, and I loved the idea of being able to

correct or alter anatomy for the benefit of the patient."

After earning a medical degree, during her residency in general surgery, Daley completed a postdoctoral research fellowship focusing on tumor immunology and the biology of pancreatic cancer. This sparked her interest in oncology. "I went into general surgery not really having an idea of what area I was going to specialize in. It was midway through my surgical training that I started spending a lot more time taking care of cancer patients. I really enjoyed it. I feel like I develop a very meaningful relationship with cancer patients."

Daley says the nature of cancer treatment often means she’s caring for people for the rest of their lives. "It goes beyond, 'How am I going to fix this medical problem?' It's, 'How am I going to get you to your next milestone?' Like your child's graduation. It's a privilege to help patients work toward a goal. Things become valuable that perhaps weren't valuable before. And if I can somehow make those things happen for patients though my care? I find that quite rewarding." After her surgical residency, Daley entered a fellowship in surgical oncology at Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, where she worked closely with patients facing pancreatic and stomach cancer.

The engineer in Daley has also led her to become a proponent of machine-enhanced, or "robotic," surgery.

"We're using more advanced technology to give us the tools we need to operate more efficiently. Additionally, if patients have smaller incisions, and less pain, then they may recover more quickly."

Daley says that these advances in surgical techniques represent a significant leap forward from the more invasive surgeries of the past. In robotic surgery, the surgeon gets many more degrees of freedom on a minimally invasive platform. You can do more complex things in small spaces that you couldn't do laparoscopically. For example, gynecological or many colorectal surgeries are performed in the pelvis, which is a very small space. And robotic surgeries can give us more technical capabilities in these small spaces. The technology is expanding the types of surgeries we can do with a bare minimum of invasiveness."

"That's the real efficacy of this platform. I guess it’s the engineer in me, but I think this is the direction surgery will be moving in future."

Continue reading Illuminate, 2023 or download the print version.

Get research news in your inbox!

Our Illuminate e-newsletter showcases the important and unique research underway at the Rogel Cancer Center.

Follow this link and sign-up today!

"It was midway through my surgical training that I spending a lot more time taking care of cancer patients. I really enjoyed it. I feel like I develop a very meaningful relationship with cancer patients."

"It was midway through my surgical training that I spending a lot more time taking care of cancer patients. I really enjoyed it. I feel like I develop a very meaningful relationship with cancer patients."